Washington Workforce Watch

The latest insights and updates from Washington’s workforce development community.

- Dec. 5, 2025

- Oct. 16, 2025

- Oct. 14, 2025

- March 24, 2025

- March 19, 2025

- Dec. 10, 2024

- Oct. 2, 2024

- May 5, 2023

- Jan. 18, 2023

- Dec. 16, 2022

- Dec. 2, 2022

Workforce Pell represents progress for both workers and employers

A new federal student aid program is a major win for both workers and employers, the Workforce Board’s Marina Parr told lawmakers Thursday.

Workforce Pell grants were approved by Congress and signed into law earlier this year. The grants are intended as financial aid for students enrolled in short-term programs that lead to in-demand jobs.

“Workers need shorter pathways to get the skills they need to give them momentum in the marketplace,” Parr, director of workforce system advancement, told the Senate Higher Education and Workforce Development Committee.

Many business groups have advocated for faster and more flexible training programs over the years.

“Employers are in need of talent now in a wide range of sectors,” Parr told the committee.

The new grants may be ready as early as July 2026, depending on when federal rules are established to manage the program.

Parr added that Washington is ahead of many other states in being prepared to evaluate employment and earnings outcomes for short-term programs, as called for in the federal legislation. Workforce Pell will provide federal financial aid for qualifying programs lasting between 8-15 weeks—a significantly shorter time frame than traditional Pell grants. Besides the shorter time frame, Workforce Pell also requires substantial employment, earnings, and completion outcomes.

The state’s Workforce Board regularly evaluates the performance of thousands of postsecondary programs across Washington to determine which programs qualify for federal training dollars through the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act (WIOA). Those performance results are published on the Workforce Board’s career and education portal Career Bridge. Results inform students, job seekers, and the public about how well education programs pay off in terms of job placement and earnings for recent graduates.

Workforce Pell could be evaluated in the same way, Parr said, using the agency’s secure, encrypted portal that already collects student-level records as part of the annual WIOA evaluation process. Eligible programs could also be flagged on Career Bridge so students could easily find short-term training programs that qualify.

“We’re ready to go on this,” Parr said. She added that the newly modernized Career Bridge was already recording over 120,000 monthly page views.

Workforce Board research staff have reviewed short-term Washington programs to see how many might qualify for Workforce Pell, under the current proposed parameters. One hundred short-term, career-focused programs appear to meet employment and completion thresholds laid out in the federal law, Parr said. This includes dental assisting, emergency medical technician, information security, and machining technology and other training.

The Workforce Board, State Board for Community and Technical Colleges and Washington Student Achievement Council are working with the Governor’s Office to coordinate the new program’s rollout in Washington.

Workforce Board, partners make progress on coordinated service delivery for job seekers

A project to help job seekers find employment and services more efficiently is making significant progress, Workforce Board officials report.

Several early milestones have been reached in the No Wrong Door project, which aims to create a new and unified way for job seekers to access Washington’s workforce system.

Washington’s workforce system supports more than 531,000 customers in at least 20 programs managed by several state agencies. The system’s ability to efficiently and effectively provide a coordinated and streamlined customer experience is restricted by operational silos, including limited information sharing across agencies. Being able to find the right services across these agencies and processes can be very difficult— especially for people with multiple or significant barriers to education and employment. When customers have to repeat the process of sharing their information and often difficult stories many times, they become frustrated and may walk away from services.

The No Wrong Door project helps Washington be prepared for new changes and future demands on the workforce system.

“The No Wrong Door project will improve customer service and support a stronger, more efficient workforce system,” Executive Director Eleni Papadakis says. “These reforms will help workers find quality jobs and connect employers with skilled workers.”

This effort aligns with Gov. Bob Ferguson’s Executive Order 25-06, issued in September, to transform customer experience and service delivery of state government operations.

“Improving the lives of Washington residents through remarkable service delivery is a fundamental priority for my administration,” Ferguson wrote in the order.

No Wrong Door Project Progress

Since the program was directed via budget proviso in 2022, major progress includes:

- Completing a feasibility study on legal, technology, resourcing, and governance needs to guide a final implementation design.

- Establishing the Data Governance Council, which includes leaders and subject matter experts from seven state workforce agencies.

- Successful testing and launch of several technologies. The success of the pilot was made possible through partnerships with WaTech’s Enterprise Data Platform and WA.Gov portal initiatives. Through these two efforts, the No Wrong Door project has been able to build a data matching solution, secure data environment, and coordinated navigation tool needed for a connected workforce system.

“This initiative embodies a forward-thinking, people-centered approach to delivering services,” says WaTech Chief Data Officer Irene Vidyanti. “We are confident that the No Wrong Door project will not only transform Washington’s workforce service delivery but also serve as a model of effective, resident-centered innovation nationwide.”

Washington employers face significant challenges finding skilled workers, new Workforce Board survey shows

Many Washington employers face significant workforce challenges, a new Workforce Board survey shows, including high turnover, lack of soft skills and not enough qualified applicants for open jobs. The report also includes ideas to address these challenges.

The Workforce Board’s Employer Needs and Practices Survey shows employers have difficulty hiring for openings at all levels of their organization. Notably, some employers have turned down business opportunities, outsourced work or turned to automation in response.

“Employers continue to face widespread challenges in meeting their workforce needs, especially in recruiting skilled workers,” the survey’s executive summary reads.

The Workforce Board is required by law to survey Washington employers about their workforce needs and engagement with the state workforce system. The latest survey includes responses from nearly 3,000 employers from every region of the state, including employers of different sizes.

Survey findings, which were consistent throughout the state, include:

- The biggest challenge for employers is finding job candidates.

- A majority of employers had difficulty filling entry-, mid-, and senior-level positions.

- Word of mouth is the most used recruiting resource.

- A majority of employers are not using state workforce system resources. The workforce system can help employers find and train skilled workers.

The report outlines several ideas for policymakers and partners to consider, including:

- Support policies and investments that address workforce needs, including education and training programs, addressing barriers to employment and more information for consumers about in-demand careers.

- Expand soft skills and employability training. Soft skills include employees being on time, ready for work and working in teams, for example. Employers seeking to fill entry- and mid-level roles reported a lack of employability and soft skills as a major challenge.

- Improve employer awareness and outreach for state workforce system resources.

- Expand opportunities for ongoing employer feedback from all industry sectors and geographic regions.

Learn more about the Workforce Board’s Employer Needs and Practices Survey.

WAVE scholarship: Record number of applications from across WA; Volunteers needed

A record number of Washington students have applied for the Washington Award for Vocational Excellence (WAVE) scholarship. And now more volunteers from business, labor and the community are needed to help review this surge in applications.

When the application window closed March 17, some 570 students had applied. That’s a 71% increase compared to 2024. A new application portal, ongoing outreach and increased awareness resulted in interest from all over the state. Each of Washington’s 49 legislative districts are represented – urban and rural, Eastern and Western Washington. (There were 114 applicants in 2022, 250 in 2023 and 334 in 2024.)

Jesus Chavez-Lara, center, won the WAVE scholarship in 2023. Here, he shares his experiences with the Workforce Board.

WAVE is a merit scholarship for Washington’s top performing career and technical education students. It helps students pay for up to two years of college or training. At a minimum, students will receive about $3,900 per year, for two years, or $7,800 total under current proposals. Graduating high school seniors and certain community and technical college students are eligible to apply.

The Workforce Board has a solid base of scholarship reviewers, but more are needed. Past volunteers include small business owners, community leaders, retired educators, state officials and people from business and organized labor.

Most volunteers spend one to three hours reviewing 10 applications. Each application takes roughly 20-30 minutes to review and score. Everyone’s contributions are welcome. Learn more about volunteering here.

Washington’s skilled workforce needs are ongoing. WAVE awardees and applicants study advanced manufacturing, agriculture, technology, nursing, cybersecurity, healthcare and more. The WAVE scholarship creates a path to economic self-sufficiency for these students – and helps industry succeed with a new generation of trained workers.

Please contact us at wave@wtb.wa.gov to get started.

WAVE awardee Ashley Curtin discusses the scholarship’s impact with the Workforce Board in February 2024.

Workforce Board shares Career Bridge updates with lawmakers

Washington students and job seekers will soon have access to a modernized, one stop website with thousands of education and career opportunities. The Workforce Board’s Career Bridge website is undergoing a major redesign and is scheduled to relaunch in June.

“It’s going to be a new and improved, much more user-friendly tool,” Director of Workforce System Advancement Marina Parr told the House Postsecondary Education and Workforce Committee Wednesday.

Career Bridge is a public facing-website that helps users explore careers, look at job trends and find education all in one place. The site includes more than 6,500 postsecondary programs, including short-term training, registered apprenticeships and two and four year degrees, for example. Customers include middle and high school students, job seekers and people who want to change careers.

Notably, many of the programs featured on Career Bridge include a consumer report card that shows employment rates, earnings and more for people that went through the program. For example, students who completed the associate’s degree nursing program at Skagit Valley College reported median earnings of $75,000, a 94% employment rate and an 84% program completion rate. This work, supported by the Workforce Board’s research team, offers an independent analysis that helps students and job seekers make informed decisions.

“Because we pushed it out to this public facing website, everyone could use it, whether it was a high school student or a 55 year-old looking to retrain,” Parr told the committee.

Changes underway now include a redesigned logo and layout, dynamic, user-friendly information, a digital portfolio where users can save their searches, and upgrades to support mobile devices.

“It’s just going to be a much more dynamic experience,” Parr said.

Please visit Career Bridge for more information.

Workforce Board shares Career Bridge updates with lawmakers

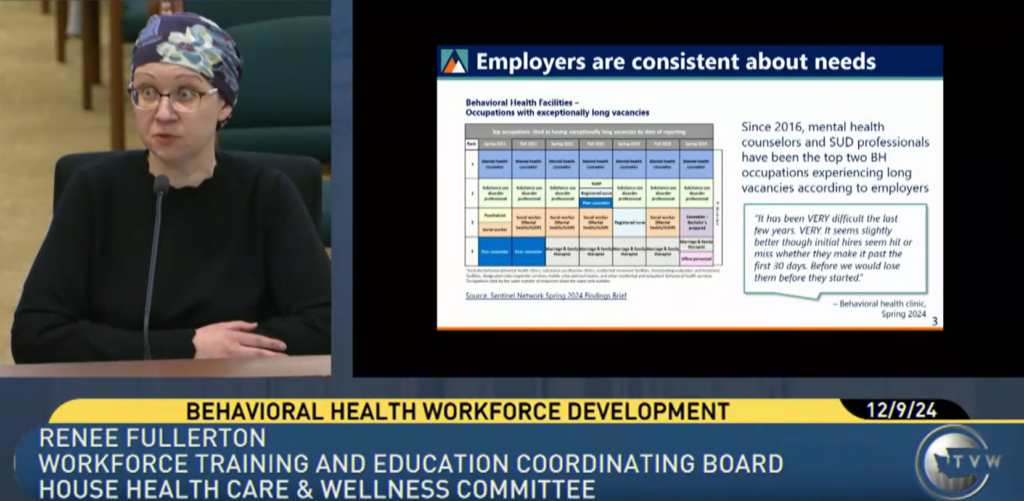

Access to good behavioral healthcare depends in part on enough workers to provide services. But Washington continues to face major shortages in a variety of professions to support those services.

Employers report mental health counselor and substance abuse professional positions are among the job openings that consistently have exceptionally long vacancies, the Workforce Board’s Renee Fullerton told lawmakers Monday.

Several factors are driving this shortage, including low pay, burdensome documentation for reimbursement, and tightly controlled state and federal laws and rules that keep some people out of the behavioral health workforce.

“These underlying workforce challenges have been in place for many years,” Fullerton, the Workforce Board’s health and policy associate, told the House Health Care and Wellness Committee.

“These underlying workforce challenges have been in place for many years,” Fullerton, the Workforce Board’s health and policy associate, told the House Health Care and Wellness Committee.

The Workforce Board has supported behavioral health policy reforms since 2016. The board brings business, labor and government partners together to explore challenges and find solutions. The agency is led by Executive Director Eleni Papadakis, and the board is co-chaired by Gary Chandler and Larry Brown, who represent business and labor, respectively.

“Washington’s behavioral health employers continue to experience a skilled labor shortage, like many industries,” Papadakis said in a statement. “But this shortage rises to a higher level of urgency as public health and safety, the ability to sustain employment or education, and the general quality of life for our people can be impacted when adequate services aren’t available.”

On the pay front, Fullerton reported some good news.

“Anecdotally employers report they have increased wages, though the cost of living has also risen, which blunts the positive impact on a worker,” Fullerton said.

Encouraging interest in behavioral health careers, reducing administrative burdens for service providers and studying the results of recent law and payment changes were among the policy ideas Fullerton shared with lawmakers.

The Workforce Board, state Department of Health and the Washington Health Care Authority and other partners are seeking employer feedback on recent legislative changes and to gather suggestions for future work in this area, Fullerton added.

Learn more about the board’s ongoing work to support the behavioral health and health care workforce.

Workforce Board highlights reentry services

Buffy Henson rebuilt her life. She left prison custody on July 6, 2016, and had a job interview on July 9. Two major factors helped make that happen: Washington’s reentry services and an employer willing to invest in formerly incarcerated workers.

Henson shared her story at the Sept. 26 Workforce Board meeting, which focused on reentry services for people involved with the justice system. Research shows that people who find employment after incarceration are much less likely to end up in prison again, which is costly for taxpayers and damaging for families.

Buffy Henson, left, Jim Chambers and Sioeli Laupati speak to the Workforce Board about their reentry experiences at the Sept. 26 board meeting.

Henson started work a few days after her interview. She held the job for seven and a half years before moving on to another employer. Education, training and support from the state Department of Corrections helped her build a strong foundation for success.

“Life is good today,” she told the board.

Henson’s success is a bright spot in the larger story of second chance hiring in the U.S. Today, one in three adults have a criminal record and 1.25 million Americans are in prison – the highest number of incarcerated people in the world.

“More people in prison means less people working,” a recent U.S. Chamber of Commerce report reads.

And less people working fuels the nation’s ongoing skilled labor shortage.

“This shortage is affecting all industries across nearly every state,” according to the report. “Even if every unemployed worker filled an open position in their industry, well over a million jobs would still remain vacant.”

The report highlights a major opportunity for Washington and other states: There are millions of people formerly involved with the justice system looking for work. And there’s a nationwide skilled labor shortage across every industry.

But too often, formerly incarcerated people face challenges finding work after release. The U.S. Chamber of Commerce notes six of 10 people were jobless from the time of release to four years after release.

Jim Chambers, a formerly incarcerated person who now helps people with reentry services, recommended employers support peer mentoring. Many people suffer from trauma of being incarcerated post-release.

“Partners need to understand what these people are going through,” Chambers said.

The board also heard from Secretary Cheryl Strange of the Washington state Department of Corrections. The department’s Reentry Services Division shows Gov. Jay Inslee’s commitment to the issue: 800 FTEs, a budget of $154 million, and reentry services in all 11 prisons and 12 Reentry Centers. Services include robust education, treatment and work readiness programs. Post-release, 108 navigators help people connect with jobs, housing, healthcare, parenting support and more.

Co-Chair Gary Chandler, left, asks questions at the Sept. 26 Workforce Board meeting.

That’s just a snapshot of the many efforts to reduce recidivism, supported by a broad coalition of partners throughout the state. Inslee has challenged state agencies, board and commissions to better help formerly incarcerated people successfully reenter society through a new executive order.

Workforce Board Co-Chair Gary Chandler stressed that employers are a critical part of the equation, and stressed the need for stronger partnerships between state government and industry.

“We need businesses to step forward,” Chandler said.

Watch the board meeting here on TVW.

Research team highlights significant income gaps at Workforce Board strategy meeting

Washington’s economic success has earned accolades here and across the country. But there’s more to the story beyond great technology, manufacturing and other jobs, often concentrated in King and Snohomish counties.

“Washington’s economic strength does not mean success for everyone,” said Dave Wallace, research director at the Workforce Board. “A closer look at the data shows major disparities throughout the state.”

Wallace and other researchers from the Workforce Board shared a detailed economic report to kick off the board’s 2023 strategic retreat Thursday.

Principal Researcher Coral Garey shared what’s considered a living wage for one adult and one child in Washington: $80,000 a year or more, as reported by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Living Wage data. Yet 72 percent, or nearly three-quarters of Washingtonians, earned $80,000 a year or less, the most recent U.S. Census data shows.

“I want you to think about not only the data I show you, but the impact these income levels have on Washingtonians’ everyday lives,” Garey told Board members. “These aren’t just numbers on a screen – they’re the lived experiences of our community.”

The percentage of Washington workers earning more than the living wage were captured in the following categories:

- $80,000-100,000 a year—8% of workers.

- $100,000-200,000 a year—15% of workers.

- $200,000-500,000 a year—3% of workers.

- Over $500,000 a year—1% of workers.

Washington’s housing shortage was also discussed at the meeting. A Washington worker needs to earn at least $65,000 a year to afford a two-bedroom apartment at market rent, Garey said. This “housing wage” reported by the National Low Income Housing Coalition assumes workers pay 30 percent or less of their income on housing.

There are also considerable income gaps between urban and rural Washington. Some 39 percent of workers in King County make more than $80,000 a year. In South Central Washington, which includes Yakima, Skamania, Klickitat and Kittitas counties, only 13 percent earn that much.

And income gaps between men and women remain significant. Women make up more than half of the income bracket for those making less than $20,000 a year. The share of women among all income brackets steadily decreases as income rises.

The Board’s two-day retreat continued Friday, May 5 at the Hotel Murano in Tacoma.

Watch Thursday’s portion of the meeting here:

https://www.tvw.org/watch/?clientID=9375922947&eventID=2023051035

Workforce leaders support new clean tech jobs

New industries mean new jobs and opportunities.

Workforce Board co-chair Larry Brown on Tuesday testified in support of House Bill 1176, which creates the Clean Technology Workforce Advisory Committee.

The bill requires the Workforce Board to identify ways the state can support clean energy workforce training programs at every level, from apprenticeships to community colleges and more, Brown told the House Postsecondary Education & Workforce Committee.

“Having passed transformational clean energy policies in recent years, it’s very timely for the state to be getting organized around this topic,” Brown told lawmakers.

Washington’s Clean Fuel Standard kicked in on Jan. 1. Lawmakers have also passed the Climate Commitment Act, which creates a new cap-and-invest program. Both measures aim to cut greenhouse gases by creating incentives for businesses to adopt new technologies, among other measures.

Where will the workers come from to drive these changes? And how will the existing energy workforce be impacted? That’s where the Workforce Board comes in.

The board will work closely with employer and worker stakeholders to understand what skills are needed. The board will also consult with education and training partners to identify what programs already exist or can be adjusted – and when new training should be created entirely.

“Clean energy technology jobs are being created every day,” Brown said. “…As technology advances, new skills will be needed by our workers and used by our businesses.”

Brown listed a new battery materials plant in Moses Lake and opportunities in hydrogen energy as examples.

The Workforce Board has a long track record convening stakeholders to solve problems, explained Nova Gattman, the agency’s deputy executive director.

“We stand ready to support this effort by leveraging our expertise as an organization that brings together a range of diverse groups and working to develop policy recommendations to address challenging workforce issues,” Gattman said.

House Bill 1176 is sponsored by Rep. Vandana Slatter, D-Bellevue, who chairs the House Postsecondary Education & Workforce Committee.

The Workforce Board has voted unanimously to propose this stakeholder strategy to Gov. Jay Inslee and the Legislature. Brown testified Tuesday on behalf of the Workforce Board and with the support of Workforce Board Co-Chair Gary Chandler, who was unable to attend. Chandler is a vice president at the Association of Washington Business. Brown is the past president of the Washington State Labor Council. The Workforce Board is a unique coalition of labor, business and government leaders working together so that every Washington community thrives.

Low wages, student debt drive shortages in behavioral health workforce, experts say

Low wages and high student debt levels are driving shortages and turnover among counselors, social workers, psychologists and other behavioral health workers in Washington, a new report shows.

Experts recommend state lawmakers consider two strategies to fight the ongoing shortage in Washington’s behavioral health workforce: Help raise wages and address student loan debt. A recent report shows some mental health counselors have average loan debt of $145,000, and make about $59,000 a year, for example.

These strategies were recommended by the Behavioral Health Workforce Advisory Committee in a new report. The committee includes many of the state’s leading behavioral health care experts and is one of several that advises Washington leaders on current workforce challenges and solutions.

Washington’s Workforce Training and Education Coordinating Board (Workforce Board) has led efforts to address behavioral health workforce barriers since 2016 and manages this advisory committee.

Demand for drug and alcohol counseling and mental health services has increased since the pandemic. At the same time, a lack of providers has made access to this care difficult for many Washington families.

The report recommends:

- Address low wages by advocating for increased Medicaid reimbursement rates and a new statewide reimbursement plan for services funded by the federal government. This model, if adopted, would help behavioral health clinics raise wages for counselors and social workers, for example.

- Boost state funding for behavioral health education loan repayment programs.

- Increase state funding to administer and evaluate the Washington Health Corps program, which includes the loan repayment program.

- Require employers and state officials to provide more information about the federal Public Service Loan Forgiveness program to help qualifying health care workers have their federal loans forgiven after 10 years.

- After studying results of a pilot project, fund scholarships for behavioral health students who agree to work in facilities that serve Washington residents with the greatest needs after graduation.

- Increase awareness that providers who work in community settings such as homeless shelters and supportive housing can count those hours toward loan repayment programs.

“Wages and student loan debt are major barriers to solving Washington’s behavioral health workforce shortage,” says Eleni Papadakis, executive director of the state’s Workforce Board. “Community clinics in rural and underserved areas are especially impacted. This means less help for Washington families when and where they need it the most. Addressing this challenge requires more than investing in loan repayment programs. We need a comprehensive strategy to both retain our current workforce and reduce the cost of education for students considering this field.”

The report also analyzed the results of the state’s investment to strengthen the behavioral health workforce in recent years.

The state has twice moved to increase federal Medicaid reimbursement rates; increased investments in the student loan repayment program for behavioral health providers; provided relief funds for community-based clinics; and created new programs to help primary care doctors connect with mental health experts and other resources to help patients.

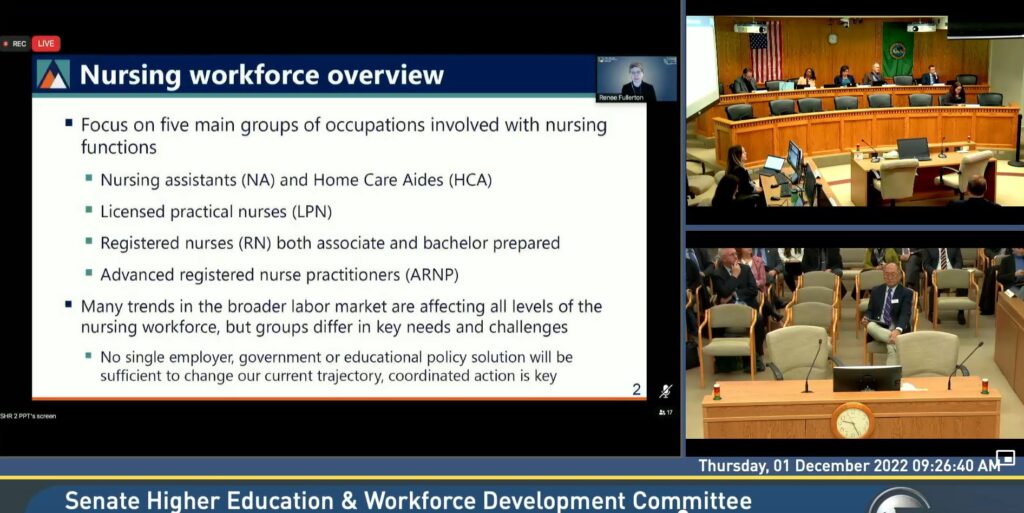

Washington needs broad strategy to fight nursing shortage, Workforce Board experts say

Washington needs a broad range of tools to fight the state’s ongoing nursing shortage, experts from the Workforce Training and Education Coordinating Board testified Thursday before a legislative committee.

Much of the attention on this challenge is currently focused on education and training, the Workforce Board’s health care policy expert Renee Fullerton told the state Senate Higher Education and Workforce Development Committee. But the problem is much bigger than that.

The nursing workforce has been impacted by sickness and death from Covid-19; lack of affordable, quality child care; burnout, stress and safety concerns; a lack of qualified applicants and competition with other industries, among other challenges. These problems have placed a new emphasis on retaining the existing nursing workforce, not just efforts in training a new one.

“To address our current nurse workforce challenges, we need a coordinated policy response with work in multiple areas by different groups,” Fullerton said. “Actions just by government, just by employers, just labor groups or just the education systems won’t be enough to move us where we need to go in Washington.”

Fullerton is a policy associate at the Workforce Board who coordinates the state’s Health Workforce Council. She left lawmakers with several recommendations for a stronger workforce, including:

- More research on how Covid-19 has impacted the workforce

- Support for child care and other caregiving

- More employer support around burnout and stress

- Adequate staffing and personal protective equipment

- And better wages for nursing assistants, long-term care workers and other health care workers.

Washington’s nursing shortage continues to pose challenges for hospitals, clinics, and patients. A 2021 survey from the Washington State Hospital Association found 6,100 nursing positions were vacant at 80 hospitals across the state, The Spokesman-Review reported. There are more than 101,000 registered nurses with an active Washington license, the Washington Center for Nursing reports. However, child care and other challenges mean some of those people are not working in health care.

Student debt a challenge for healthcare workers

Fullerton also highlighted some of the financial challenges facing students. Using small data sample, the average student loan debt for nurse practitioners in 2022 was $94,345, according to the Washington Student Achievement Council. Registered nurses had an average debt of $43,941, and licensed practical nurses had loan balances of $26,446. The data came from 101 health care workers who applied to the Washington Health Corps, which offers student loan forgiveness to professionals who serve in critical areas.

“This offers just a snapshot, but it helps demonstrate how debt is carried by those across the licensed nursing profession,” Fullerton said.

Aging population puts pressure on long-term care

Lawmakers also heard from Donald Smith, PhD, the Workforce Board’s long-term care policy manager, who highlighted the staffing challenges in Washington’s long-term care workforce.

Staffing challenges have been made more difficult since the start of the pandemic, he said.

“Furthermore, the challenges are spotlighted by a growing population of baby boomers that will require increased long-term care services over the next couple of decades,” Smith said. “This increased demand will overwhelm the existing workforce capacity without a consistent stream of professional and paraprofessional direct care providers.”

Smith leads the Workforce Board’s long-term care policy project that is creating a new licensed practical nurse apprenticeship program to help certified nursing assistants grow their careers and move forward as licensed practical nurses, among other policy work.

The Health Workforce Council meets Dec. 8 at 10 a.m. to discuss the healthcare workforce challenges and more. See the agenda here. Contact Fullerton at Renee.Fullerton@wtb.wa.gov for more information.

Contact Smith at Donald.Smith@wtb.wa.gov for more information about the Long-Term Care Project.